The war in Ukraine has had already had a devastating impact upon the nations people, and now the conflict’s effects are now spreading to other areas of life such as the food supply. To explain why the invasion is set to cause a global food crisis, here is analysis from Josh Butler.

Ukraine and Russia both have a proud history of producing wheat, and this was celebrated in their political posters.

The sun is shining, covid restrictions are a thing of the past and summer has begun to arrive!

You want to get outside and enjoy the good weather, and spend time with friends; so you plan to host a barbeque. In preparation for your summer festivities, you go to your supermarket of choice; and set out to find strawberries for Pimms, meat for the grill and fresh bread…but everything you are looking for is either not there or much more expensive than you expected.

Why are we set to have price rises for bread and severe shortages of seasonal fruit and veg? The War in Ukraine.

Unless you have completely buried your head in the sand for the past few months, you will have heard about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. You will have seen the destruction from missile strikes, heard about the sanctions placed upon Russia, heard the plight of Ukrainians trying to flee the conflict, and heard about the importance of Russian oil to Europe. But you may not know about the way the war will affect global food production.

Ukraine and Russia produce 30% of the world's wheat exports, and in turn this has collapsed. With the United Nations estimating that a similar percentage of Ukrainian farmland will become an active war zone, and millions of Ukrainians who would normally be tending the fields are now instead trying to escape or fighting on the front line, and now that we are over 100 days into the conflict, wheat supplies are definitely not on track to recover quickly.

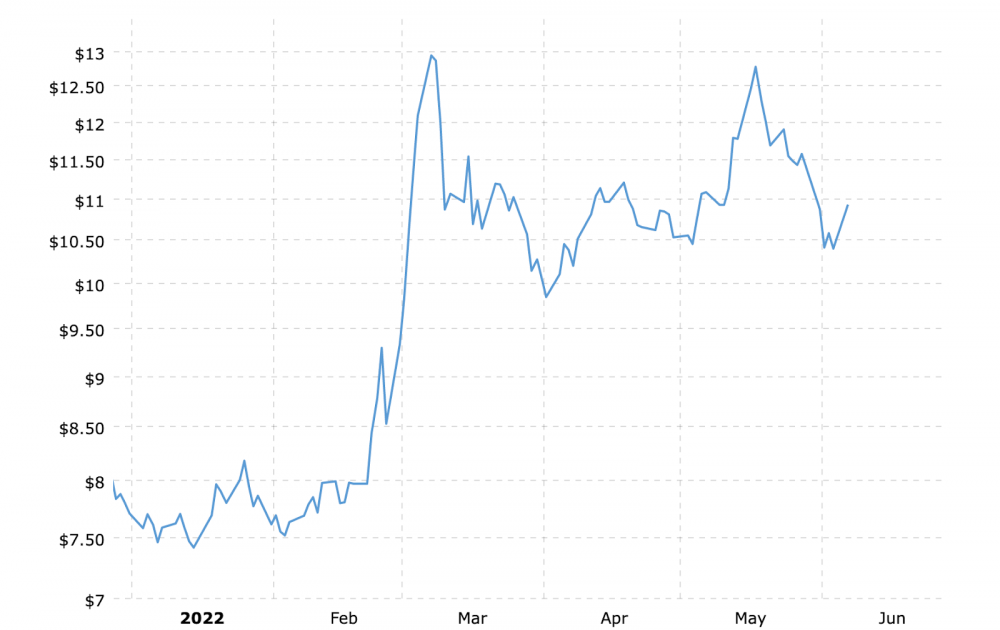

This sudden loss of the “Bread basket of the world” has had a huge affect on wheat prices, as the supply of Ukrainian wheat disappears from the global market. In the graph below, you can see how prices have jumped since the invasion began in February.

by 50%”, Mr Holsether, head of Yara international said to the press in March after their offices in Kyiv were hit by a missile.

Yara is one of the world’s largest fertiliser producers, and they rely on a steady supply of natural gas to create ammonia, a key ingredient in common fertiliser. They got this fuel for their European factories from Russia. Fuel prices were already on the rise, which led to price rises for the cost of fertiliser, and that was before the conflict began. At one point, fuel prices got so high in Europe that they reduced production to 40% so that their business could keep going.

These changes are already having effects on the price of fertiliser in the UK. Head of the National Farmers’ Union, Minette Batters said that: “Last year I paid under £300 a tonne for nitrogen fertiliser; this year it’s over £700 a tonne”. At some point soon, these production

costs will affect the price of food on the shelves.

As the cost of producing wheat increases, so will the cost of raising livestock. Animals are fed with wheat, and animal feed prices have already risen by 39% in the last year, and that is before the effects of the current crisis. The rise in feed prices and fuel costs mean that it now costs 50% more for every chicken that is raised. So don’t be surprised if your favourite steak or weekly shop for chicken costs more in the coming months.

There are multiple factors leading to greater food poverty at home and abroad, including the effects of inflation, supply chain struggles and the worsening cost of living crisis. If you didn’t already know about food poverty, it may have come to your attention during Covid because of Marcus Rashford’s campaign to keep Free School Meals going during the holidays. His focussed political efforts expanded into a wider campaign to reduce food poverty in the UK. Approximately one in five people in the UK currently live in poverty, and many of those people will have faced the choice between going without food or going without heating throughout the winter.

Marcus Rashford, footballer and food poverty campaigner

Food poverty stretches far beyond the UK though. In the last two years, there has been an estimated increase of 100 million people who go to bed hungry, and this current crisis will only make the situation worse. Armenia, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, and Eritrea are all countries that get almost all of their wheat from Russia and Ukraine and are now scrambling to find new exporters. These nations know all too well the effect that rising prices and empty shelves can have. Rising food prices have caused social and political upheavals throughout history, and many African and Arab countries try to subsidise the price of bread to secure support from their voters. However, as the pandemic has affected their financial ability, they are struggling to keep the prices of bread low. It was rising bread prices that helped spark the Arab Spring in 2011, and we are already seeing similar street protests in Morocco now.

This crisis will not be solved with a simple solution. But there are actions that can be taken to alleviate its effects. In the short term, the National Farmers Union is urging the Government to take urgent action to help British farmers. They want to be assisted in their efforts to produce food to keep supermarket shelves stocked and reduce the threat of further price rises. They would like the Government to help farmers source fertiliser, perhaps subsidising the cost of wheat so farmers can keep production going, and granting more visas to the Seasonal Workers Scheme to provide farms with the labour they need.

In the medium term, we need to be able to create fertiliser of our own. But we are currently going in the other direction, with Britain’s biggest fertiliser producer, CF, closing one of its plants due to rising fuel prices. They are currently a central pillar in the UK food supply chain, supplying fertiliser for farmers as well as carbon dioxide which is vital for slaughtering livestock, preserving food and carbonating drinks.

Tony Will, CF’s chief executive, has said that they cannot keep the plant open whilst staying operational around the rest of the UK. Farmers have argued that whilst it makes sense for CF to close the plant to preserve profits, it will lead to further difficulties in providing fertiliser for farming. There is a case to be made that the British government should nationalise any fertiliser plants that are at risk of closing.

In the long term, we will have to reimagine the way we grow, sell and eat our food. This current fertiliser crisis caused by the war in Ukraine have reinforced some of the worries environmental groups have about modern farming. They say that we need to move away from

intensive, fertiliser dependent farming and back towards traditional methods, which would allow us to grow food without being dependent on Potash supplies from Belarus. This is easier said than done, and would also require us, the British public, to rethink the way we look at and shop for food. The convenience of the modern supermarket, with food available all year round, imported from across the world, and sold at moment’s notice, may become a thing of the past.

Your Comments

Be the first to comment on this article

Login or Register to post a comment on this article